Along the Nile, beyond history

While the world's longest river laps a landscape where nature, myth and memory are one, we gaze in fascination at the life that animates its banks, today as it did three thousand years ago

They sleep locked in a shrine at the Crocodile Museum next to the Kom Ombo temple, behind glass that would shatter instantly if from death suddenly rebelled. For the millennia could do nothing against their woody, sharp scales, their mighty bodies brown as logs beached in the sun. And even the sharp eyes appear no less alive than they did when these reptiles were not yet dead, three thousand two hundred years ago, before the Egyptians mummified them and laid them in the necropolis of this site originally consecrated to Sobek, the crocodile god, the ruler of the flood, the one who from his own sweat makes the Nile flow from its sources to the Mediterranean.

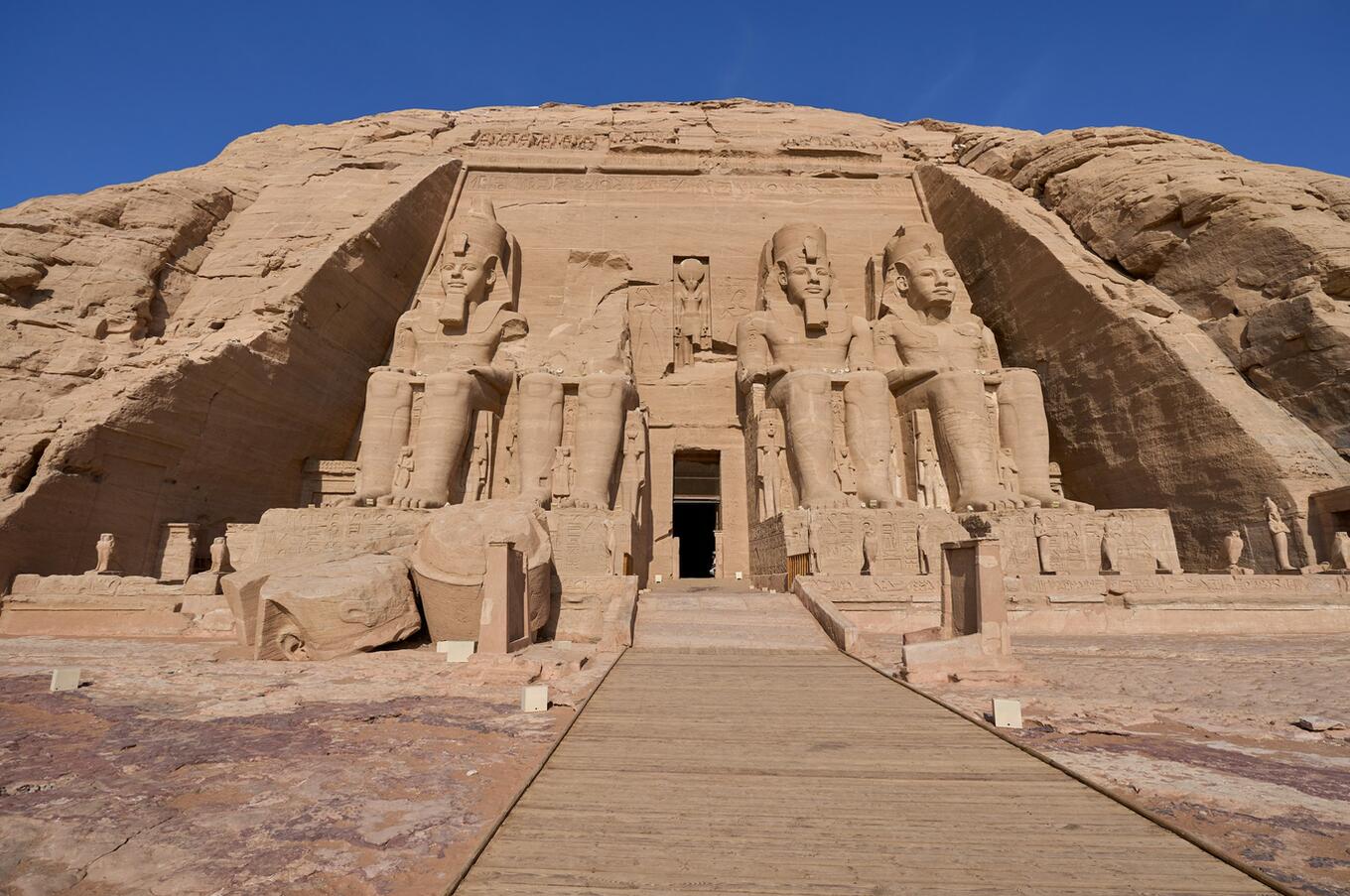

And one must always remember this while cruising aboard a traditional boat or dahabeya: a cruise on the world's longest river is not a shortcut (albeit a gentle one) to touch without traffic the magnificence of temples and necropolis, from Luxor and Karnak to File and the unforgettable Abu Simbel, the temple of Ramses II built on a rise in Lake Nasser, where crocodiles still haunt the waters and wreak havoc on perch, and only certain Nubian families dare to catch them and keep them in their homes, as pets and auspicious amulets.

Sailing on the Nile is to forget history or rather, to blend it into nature, poetry, religion and myth. To spend hours at the bow watching life dancing on the water, and to imagine where the mountain ranges that of the Nile form the valley start and end. Wondering why that blue color is so much maritime and so little river, plied by the barges and small boats of the tilapia fishermen, always and only two aboard, one paddling and the other casting nets, one beating the water with a wood to build a trap of bubbles around the fish, and the other finally lifting the spoils.

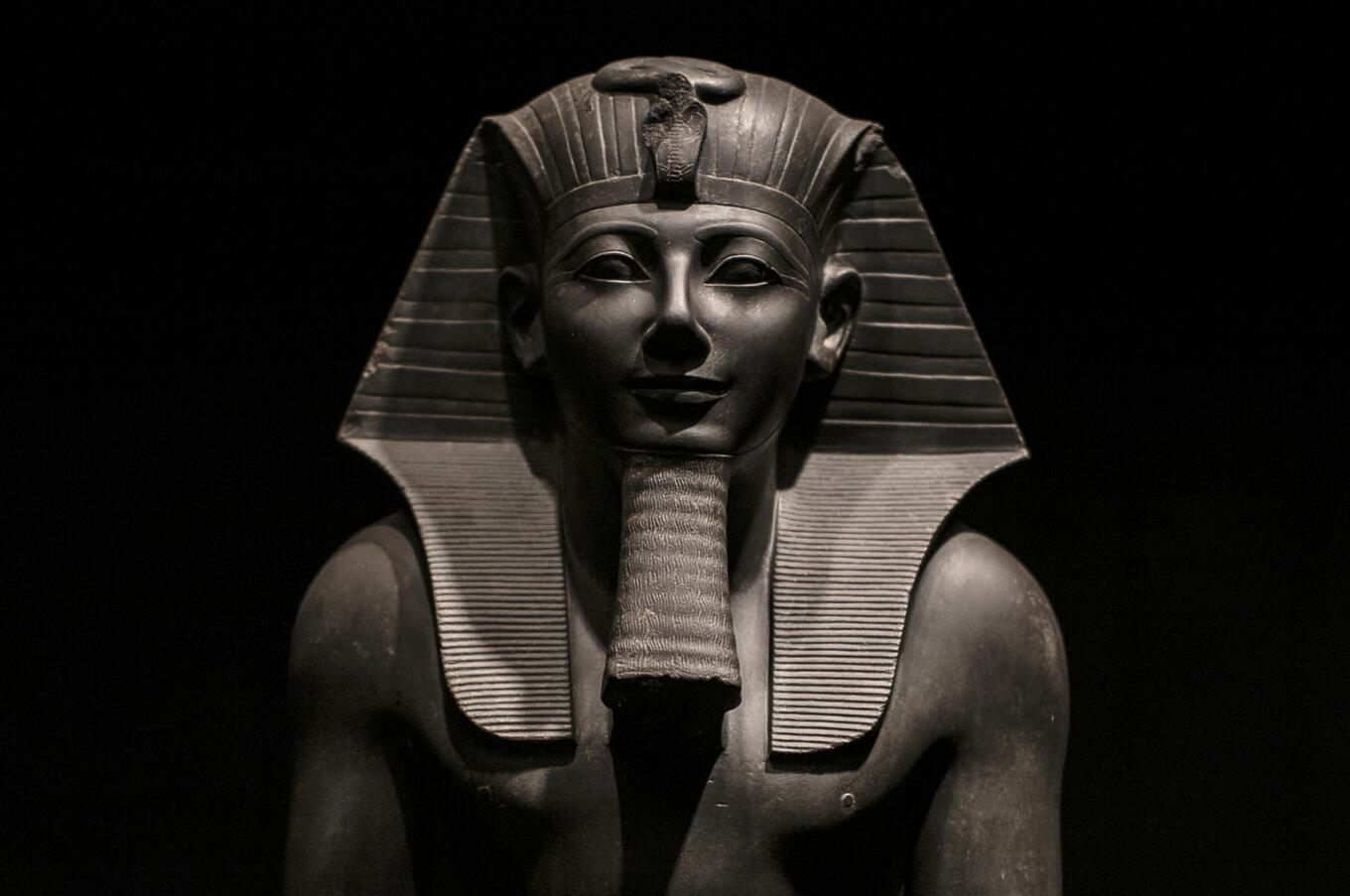

The magic is not just getting lost in this centuries-old order. But to make the hieroglyphics and wall paintings seen during the stops, Cleopatra VII and the Book of the Living, the Book of the Dead and the Book of Doors, come alive in the mind like cartoons. And so, resuming navigation at sunset after visiting the Valley of the Kings, the sky suddenly begins to tell another story.

And it's nice to play at thinking that the world you see is the same world a peasant or a scribe saw, as the empyrean is made in the image and likeness of the vault frescoed in the tomb of Ramses VI, that starry sky over which is stretched the goddess Nut depicted as she gives birth to the sun at dawn and swallows it up at sunset. And then - I saw it painted on a wall in the tomb of Seti I - the sun disk itself is no longer a star but a living thing, generated by the sacred scarab that gives it form with its front legs and with its hind legs pushes it up, until Horus puts his falcon mask on its face and closes the circle of day and night.

The success and charm of a Nile cruise depends in large part on the vessel. We traveled from Luxor to Aswan aboard a dahabeya, as did nineteenth-century explorers and, millennia earlier, the ancient Egyptians. Modeled after the ancestors painted in the tombs of the pharaohs, it retains the original agility with all the added furnishings and conveniences for comfortable travel. It has a flat bottom, like a barge, and is fitted with two masts with triangular sails, one at the stern and one at the bow. Due to its moderate tonnage, it can accommodate a very small number of guests and, most importantly, dock even in the ports of smaller locations, which are not accessible to large cruise ships.

The ancient Egyptians gave their paradise a name; they called it the Fields of Iaru. It is depicted in a tomb in the Valley of the Artisans, and it is exactly that: a river, rushes, land on which to plant alfalfa and vegetables as soon as the Nile recedes, children bathing far from the shore and when the boat passes they wave with full force, rising up to the belt like water polo players before scoring a goal. There are the ever-solitary grey herons, who when they find a floating cushion of branches drift with the current, strutting and aloof, "the sad kings" of Arabic literature. On islands in the middle of the river graze the buffaloes that donate the fatty milk to make samn baladi, the clarified butter for frying broad beans and making falafel. And flying ibis, protectors of hieroglyphic writing and medicine, which just like the crocodiles were sacred and stuffed by the millions, found in the little-known necropolis of Tuna El-Gebel. On the east bank, that of the living, and on the west bank, that of the dead, palm and mango trees are constantly switching places. And between the fronds rise rivulets of smoke created by farmers as they burn the waste from sugarcane processing into ash that fertilizes the fields.

Smaller boats can approach the shores and stop on the islands in the center, where animals graze and small farming villages spring up, and a social life is consumed on the benches outside the houses where families gather to laugh and talk. "Only those who have beautiful eyes can see beautiful fabric weave," says Hasan, in his traditional cobalt blue suit, the elder who leads the council of wise men. From his house a staircase descends to a bulrush, quite like the one described in the Bible where the basket of Moses, an infant, became entangled before being rescued by Pharaoh's daughter at Yahweh's behest. And once again every element of nature is transfigured into myth. And everything appears exactly as it is. While nothing, at the same time, is only what it seems.