Clarence Terhune, history's first air stowaway

The 1920s were marked by the golden age of silent films, Prohibition, and the rise of organized crime, a decade where even stowaways could achieve a certain notoriety, especially aboard ocean liners.

With the arrival of the great Graf Zeppelin airship and the promise of transatlantic flight, a new and uncharted frontier opened for the boldest of them all: the airborne stowaway. Unlike on ships, sneaking aboard an airship was a completely unknown game, one that demanded courage, nerve, and just the right amount of recklessness. Qualities that, in many ways, defined the spirit of the era.

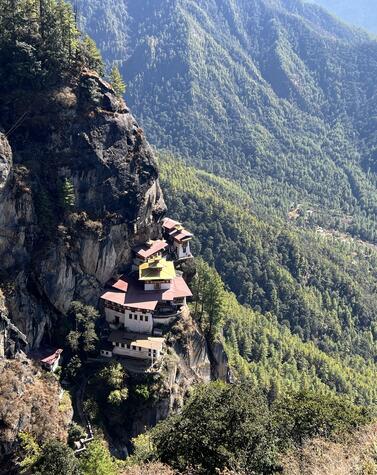

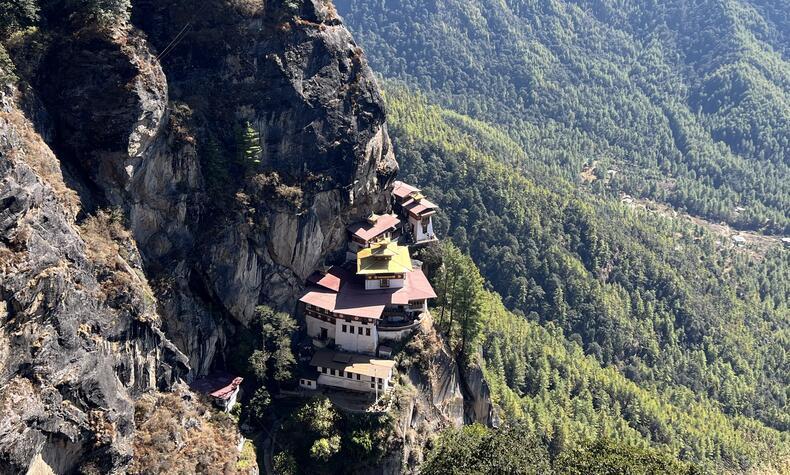

The Graf Zeppelin

At that time, taking to the skies was within reach of only a few. Airships were a sign of luxury, privilege, and high class. A trip in an airship was a luxury experience, only comparable to sleeping in first class on a sleeper train, but only this time doing it while floating in the sky.

The cabins were designed to accommodate ten passengers and included two bunks that could be transformed into seats during the day. Still, it wasn't all luxury; passengers also had to be prepared to face the cold, as there was no heating and they flew through the clouds.

Despite this, the experience of traveling on the Graf Zeppelin was indelible. The fact that you were soaring through the sky, the panoramic views, the delight of the dishes served in the restaurant, or even the chance to meet other passengers in the common lounge.

Clarence Terhune was a 19-year-old American golf caddie from St. Louis, Missouri. He was in the habit of stowing away on trains and ships, and even traveled the country, from California to Alaska, as a stowaway on a government cruise ship. Upon seeing the large airship that was to cross the Atlantic, he made a bet with his brother-in-law that he could top his previous exploits and do it in an airship.

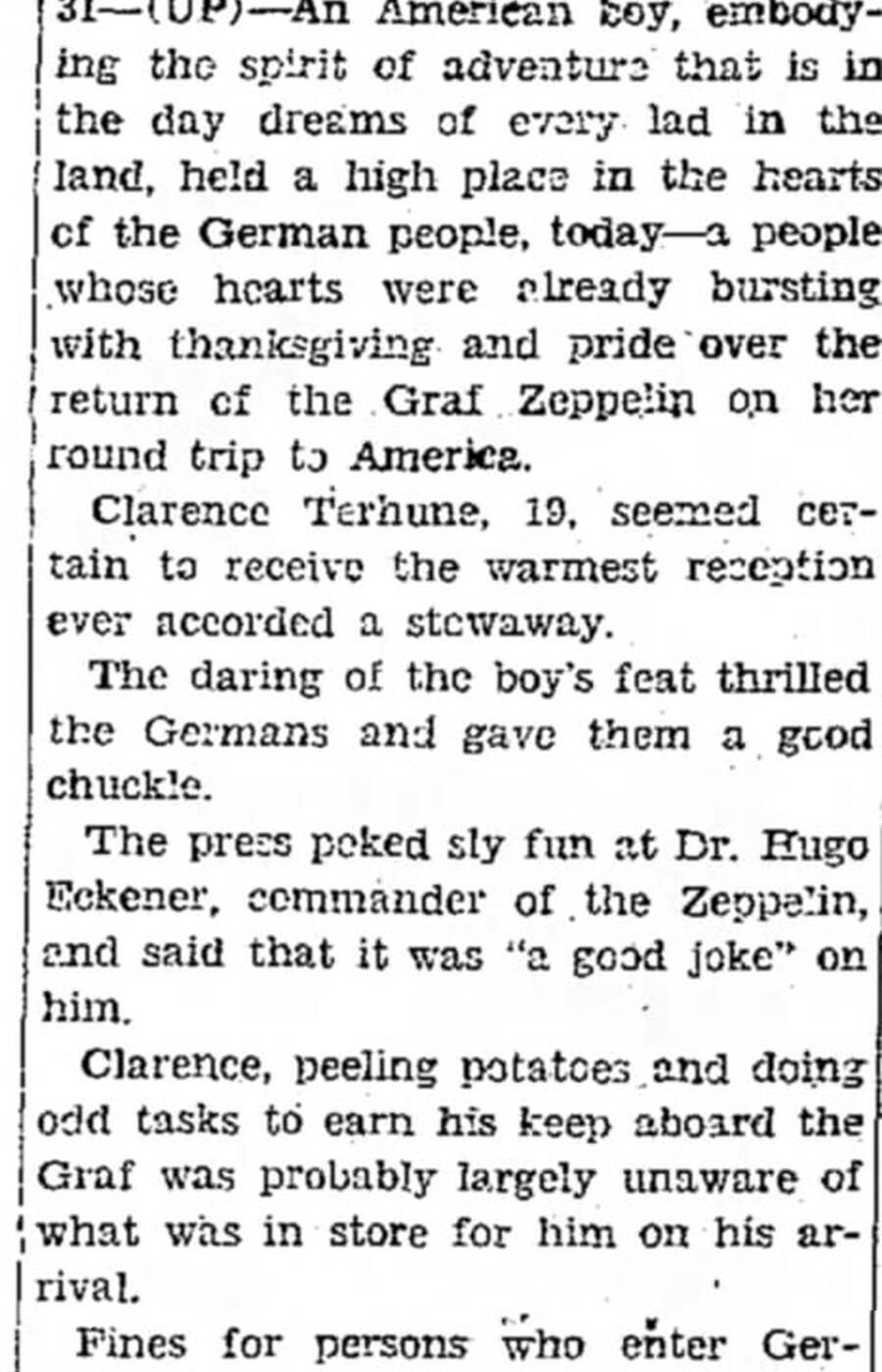

Terhune took advantage of an oversight to sneak into the imposing airship, but little did he know that his first hiding place would have to be the mail compartment. During the flight back to Germany, he was discovered and, instead of being expelled, he was put to work as a cook to pay the cost of his ticket. He washed dishes, peeled potatoes, and did all sorts of chores to gain the trust of the crew and avoid being disembarked. This is how he completed his journey to the mainland.

When the airship touched land, Clarence Terhune was arrested by German police. Entering Germany without a passport carried a fine of 20 to 10,000 marks. Still, to the German population, he became a hero; he was invited to dinners, offered jobs, and, according to the New York Times, 14 girls proposed to him.

His adventure was so well recognized that several newspapers wrote about him. The New York Times commented that "a curly-haired, 19-year-old adventurer rose to prominence such as he had never known yesterday by becoming the first stowaway on a transatlantic airliner." The Chillicothe Constitution-Tribune wrote that "The audacity of the boy's feat thrilled the Germans and gave them a good laugh."

After a stint in Germany, far from his homeland, Clarence finally embarked on his return voyage to the United States aboard the majestic French ocean liner SS Île-de-France. When the ship docked in the United States, Clarence returned to his native country ready to face the new challenges and opportunities that awaited him.